Daryl Mahon, Takuya Minami, (G.S.) Jeb Brown

Abstract

This is the second of two articles that examine the psychometric properties and treatment outcomes associated with two measures of the therapeutic alliance in naturalistic routine settings.

Methods:

Data were taken from the ACORN database for youth, and, where available, parent/carer, attending for psychotherapy treatment in naturalistic settings (N= 12,573). The sample, the largest to date, included only those completing both an alliance measure and an outcome measure at every session. Two sets of three different alliance items are used across the two populations in routine practice.

Results:

Analyses revealed that the alliance explained no more than 3% of the variance in outcomes. Alliance measures exhibit ceiling effects, and as such, drawing conclusions about correlations with outcomes can be difficult. Any drop in alliance score as rated by both youth and parent/carer is predictive of outcomes, with parent/ carer ratings being marginally more predictive. Where the alliance is rated as better by youth or parent/carer in comparison with ratings as worse, effect sizes are up to 50% better for the youth. Conclusion: The therapeutic alliance remains an important non-specific treatment component; however, measures of the alliance have ceiling effects. Both youth and their parent/carer can provide important feedback to the therapist, and any drop in alliance is predictive of clinically meaningful change. As such, therapists should monitor the alliance with both youth and parent/carer. Implications for practice, training and research are considered.

KEYWORDS alliance–outcome correlation, therapeutic alliance, therapeutic relationship, working alliance, youth and parent alliance

1 | INTRODUCTION

The therapeutic alliance, also referred to as the therapeutic relationship, is one of the most studied aspects of psychotherapy research (Norcross & Lambert, 2019). The therapeutic alliance is often operationalised using Bordin's (1979) conceptualisation of the bond, task and goals, while others define it in terms of the affective and collaborative aspects of the client–therapist relationship (Elvins & Green, 2008; Shirk & Saiz, 1992). Prior meta-analyses have demonstrated small-to-medium effect sizes in the alliance outcome correlation for youth (Karver et al., 2019; McLeod, 2011; Shirk et al., 2011). Therapists exhibit differences in their ability to cultivate and maintain the alliance with adults (Baldwin et al., 2007; Wampold & Owen, 2021). However, two meta-analyses in youth psychotherapy demonstrate that therapist variability in alliance is not associated with youth outcomes (Murphy & Hutton, 2018; Roest et al., 2023b). Prior research indicates that a poor therapeutic alliance is a predictor of premature dropout in youth psychotherapy (de Haan et al., 2013), while O'Keeffe et al. (2020) point to ruptures in the alliance as a risk factor for early termination.

In adult psychotherapy, meta-analyses suggest that the alliance accounts for between 5% and 8% of the variance in outcome (Flückiger et al., 2018; Horvath et al., 2011). However, in youth psychotherapy, meta-analyses have suggested that the variance in outcome is smaller.

McLeod (2011) has demonstrated that the therapeutic alliance explains approximately 2% of the variance in youth psychotherapy outcomes. It is not clear why the alliance outcome variability differs in both populations, although one reason could be that young people experience the alliance differently from adults (Roest et al., 2023a; Shirk et al., 2010; Zack et al., 2007).

The young person's treatment experience will be different to general outpatient adult psychotherapy that largely occurs in a one-to-one setting. Young people may have others involved in their treatment from schools or the community, or they may be in some type of residential facility (Duppong Hurley et al., 2013; Roest et al., 2023b). It is suggested that children and adolescents perceive the alliance positively based on their experience of trust, emotional support and kindness (Baylis et al., 2011; Campbell & Simmonds, 2011; Houlding, 2014). As such, young people may experience the alliance as an affective bond as opposed to a cognitive process (Nuez et al., 2021; Ormhaug et al., 2015; Zack et al., 2007). Moreover, the young person's age may mediate how the alliance is experienced. Shirk and Saiz (1992) suggest that cognitive limitations may prevent children from understanding the need for and the extent of treatment. Contrarily, older adolescents' agreement on the nature of the problem may cause a conflict between parents and the young person, impacting the alliance with the therapist (DiGiuseppe et al., 1996; Shirk et al., 2010).

Moreover, the parent–therapist alliance may impact the treatment experience for the child through engagement and attendance (De Greef et al., 2017; Welmers-Van de Poll et al., 2020). The most recent meta-analysis demonstrates that when parents have a better therapeutic alliance with their child's therapist, children have a better outcome of therapy (Roest et al., 2023b).

Prior meta-analysis suggests that both young people and their carers rate the therapeutic alliance more positively than their therapist and that parents rate the alliance with the therapist more positively than the youth (Roest et al., 2023a, 2023b).

It is possible that the young person has been mandated to attend therapy and sees the presenting problem differently to the parent/ carer (Langer et al., 2021), and as such, this impacts the quality of the alliance with the therapist (Roest et al., 2023a). The most recent meta-analysis of the alliance outcome correlation in family therapy would seem to support this proposition as those who attended therapy voluntarily (as opposed to mandated) had better alliance outcome associations (Friedlander et al., 2018).

Recent qualitative research indicates that different views are held on the therapeutic alliance by young people, parents and therapists, for example, the therapeutic bond, the type of techniques used and the role of the parent (Ryan et al., 2021). Despite these differences, the alliance is integral to successful psychotherapy with young people and their families (Karver et al., 2018, 2019; McLeod, 2011; Roest et al., 2023a). However, it is argued that the alliance should be measured from a dyadic or even systemic perspective, especially in family treatment (Roest et al., 2023b; Welmers-Van de Poll et al., 2020).

A meta-analysis by Karver et al. (2018) found that outpatient status and problem type moderated the outcome alliance correlation, with internalising disorders showing a larger effect than eating and substance use disorders. McLeod (2011) and Shirk et al. (2011) examined potential moderators of the alliance outcome correlation, which demonstrated that age, presenting problem, and timing of measurement all impacted correlations.

1.1 | Measuring the alliance

Most studies have measured the alliance at a single time point or several time points in relation to treatment outcome, using only these single time points or averaged scores (Karver et al., 2018; McLeod, 2011; Murphy & Hutton, 2018). There have been mixed findings with regard to the trajectory of the alliance in child and adolescent psychotherapy. For example, three studies found that the alliance remained stable across treatment for the first 6 months (Green et al., 2001; Hawley & Garland, 2008; Kazdin et al., 2005). In contrast, other research has demonstrated that shifts in the alliance are more predictive of outcomes than early alliance (Chiu et al., 2009; Eltz et al., 1995; Hogue et al., 2006). These later findings are supported by the most recent meta-analysis (Roest et al., 2023b), which found that changes in the alliance during therapy are more predictive of outcomes than measurement at a single point in time.

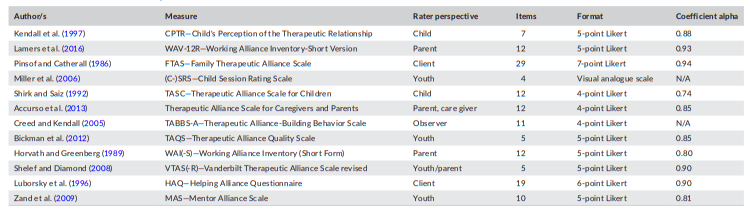

In our first article in this series of two (Mahon et al., 2023), we noted the problem of ceiling effects in adult therapeutic alliance questionnaires (Meier, 2022; Paap et al., 2019). Shirk et al. (2010) have demonstrated that ceiling effects are also present in alliance questionnaires for youth. Similarly, Bickman et al. (2010) report that the Therapeutic Alliance Quality Scale is skewed with mean scores of 4.12 on a scale of 5. According to Roest et al. (2023b), ceiling effects could also explain the small-to-moderate associations between child, parent and therapist ratings of the alliance. The extant literature exposes that across youth and family treatment contexts, there are various measures of the alliance utilised, all with adequate psychometric properties (Table 1).

1.2 | Context

This study replicates the analyses made with the adults' sample in the first article, exploring the distributions of alliance items and the implications for predicting outcomes and the use of alliance measures in clinical practice. As reported in our first article, alliance scores explained no more than 2% of the variance in outcomes for adults, due to the extreme positive skew in the alliance score distributions. This study examines the degree of skew in youth- or parent-completed alliance items and the percentage of variance explained in treatment outcome by the two different alliance questionnaires utilised in this study. If the nature of the alliance distribution is limited to the percentage of variance explained, and if the youth alliance measures have less skew than the adult measures, then the alliance is expected to predict a higher percentage of the variance.

2 | METHODS

This study used data extracted from the ACORN database, maintained by a small group of IT professionals, psychotherapy re - searchers and training content developers associated with the Center of Clinical Informatics. The ACORN clinical information system enables immediate submission of various alliance and out - come questionnaires and immediately displays results to the therapist, along with algorithm-driven clinical messages summarising change over time and drawing attention to risk indicators, such as self-reported substance use, thoughts of self-harm and changes in the alliance scores.

2.1 | Sample

At the time of this writing, the total ACORN database exceeded over 1.2 million episodes of care. For the purpose of these analyses, cases were selected based on questionnaires completed, intake scores in the clinical range, and at least two assessments. Adult outcome and alliance questionnaires were administered to those >18 years of age (N = 147,399). While youth outcome and alliance questionnaires were administered to those <18 (N = 12,573), there are no data available to permit breaking out age categories for those <18. Additionally, parent/carer completed (when available in the data) the same version of the Alliance Questionnaire as youths, and this is correlated with youth outcomes. These data make no distinction between child and adolescent, so we refer to anyone <18 as youth.

2.2 | Measurement and statistical methodology

2.2.1 | Outcome questionnaires

The ACORN processes several versions of the outcome questionnaire that have been developed collaboratively between stakeholders across clinical sites and following engagement through a partnership between academia, healthcare administrators and other key stakeholders (Brown et al., 2015; Lambert et al., 2009). Thus far, these collaborations have resulted in over 200 items with adequate psychometric properties.

Clinical sites can use these different items on outcome questionnaires that best reflect their client populations rather than being restricted to questionnaires that cannot be modified. All variations of the questionnaires are constructed to have a reliability of 0.9 or better for items loading on the general factor of global distress/wellbeing. A Global Distress Score (GDS) is calculated for all outcome measurements by taking the average of the item responses.

Severity-adjusted effect size (SAES)

In order to accommodate the multiple versions of the Youth and Adult Outcome Questionnaires, the platform uses a metric for clients' pre-/postimprovement called SAES that is statistically related to Hedge's g (Gaeta & Brydges, 2020). This is performed by linearly adjusting the GDS of subsequent measurements based on the initial severity (i.e., first GDS) and the diagnostic group, when available.

The SAES is then calculated by adjusting the global average pre-/ post-GDS change by the residual, that is, the difference between the linearly predicted change and the actual change.

Since the mean of the residualised change score is always 0, this results in SAES with a mean equivalent to the global average pre-/ postchange but with a distribution of scores around this mean that already accounts for differences in case mix. The range of SAES scores for both adult and youth measures is as follows: less than 0.5 is considered small; between 0.5 and 0.8 is medium; and greater than 0.8 is large.

This statistic is only calculated for cases with an intake score in the clinical range and at least one other assessment in that treatment episode and uses the intake score and diagnosis to adjust for differences in case mix. This model accounts for an estimated 18% of the variance in change scores. Overall, in the ACORN data warehouse, 76% of episodes are in this range at intake. Removing variance due to differences in case mix increases the accuracy of estimates of clinician and clinical effects (Mahon et al., 2023). An episode is defined as sequential GDS questionnaires with no more than a 120-day gap between any two assessments. If a larger gap is detected, then a new episode is created on the system.

2.2.2 | Statistical modelling

The SAS implementation of a general linear (Jaccard & Bo, 2023) regression model (PROC GLM) was used to perform case-mix adjustment in order for SAES to account for intake score. The use of the intake score to predict final score or pre-/postchange score is essential to control for regression artefacts (Campbell & Kenny, 1999). While diagnosis was available for less than half of the cases, questionnaires for youth are scored and processed separately from those for adults. Beyond this separation, age was not a significant predictor.

3 | RESULTS

3.1 | Alliance items and questionnaires

The following are the variable names and wording for the two sets of alliance questionnaires that appear together in questionnaires. All alliance items' variable names start with SR, an abbreviation for Session Rating consistent with common use among other measures of alliance, or session rating scales.

Alliance Questionnaire 1:

• SR1: I felt that we talked about the things that were important to me.

• SR3: I felt my counselor understood me.

• SR5: My therapy was helpful.

These three items on Questionnaire 2 were one of the questionnaires evaluated in our previous article in an adult general outpatient population.

Alliance Questionnaire 2:

• SR16: Did the session head in the direction that you wanted?

• SR22: Did you feel the counselor understood and respected you during the last session?

• SR24: This counselor and I are working toward mutually agreed upon goals.

These three items were not included in the article of Adult Alliance Questionnaires.

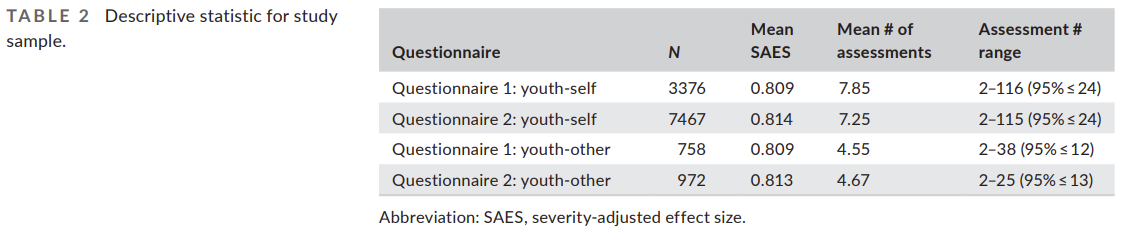

The following table is the breakdown of sample sizes and the mean SAES and number of assessments for each of the questionnaires. Note that there are no meaningful differences in the SAES scores associated with each of the Alliance Questionnaires (Table 2).

3.2 | Item analyses

As in the prior article using adult data, the first step of the analyses was to determine the distribution of item responses. All items used a scale of 0–4, with higher numbers indicating greater concerns about the treatment. The literature has identified a potential problem with client-completed alliance measures; their tendency to be heavily skewed in a positive direction thus violated the underlying assumptions of a normal distribution. This presents challenges when trying to calculate parametric statistics, such as correlations between items and correlation with outcome. Correlations between items will appear magnified, while correlations with the GDS scale and outcome (effect size) will be suppressed.

For this reason, the analyses also explore whether alliance is better treated as a categorical variable rather than as a continuous variable expressed as a scale score.

Alliance scale scores, for the purpose of these analyses, are scored as the sum of the three items, resulting in a range of 0–12. The following tables present the distribution of item responses and alliance scores at the first assessment and the last assessment in the episode. Table 3 presents this distribution of item responses and the total of item scores for Alliance Questionnaires 1.

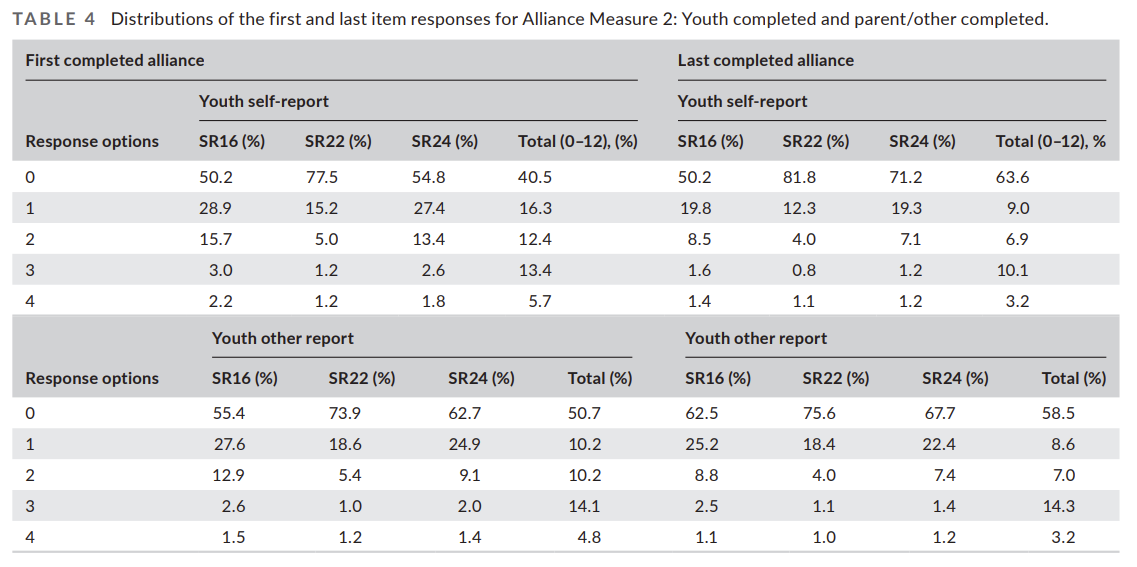

Table 4 presents the same information for Alliance Questionnaire 2.

The alliance score (sum of the three items) frequency is displayed for only the scores 0–4 to be consistent with the single-item scores. However, this is on a 12-point scale. Even so, over 80% of youth report alliance scores between 0 and 1, with roughly 50% reporting scores of 0. Additionally, over 90% of parents/carers score the alliance measure 0–1. This is evidence of the high degree of skew apparent in alliance scores.

To illustrate this point, the estimate of reliability of both of these three-item measures using Cronbach's coefficient alpha using the first assessments (higher variability) is greater than .88, an abnormally high estimate for a three-item measure, but not surprising when over half of the responses are 0 on all items and consistent with other reports of reliability for alliance measures. Similar results were found whether completed by the youth or others, both for Questionnaires 1 and 2.

Based on an analysis of our previous article (Mahon et al., 2023), it appears that adults completing alliance measures regarding therapy for a child are much more likely to report that the alliance is less than perfect compared with adults in therapy for themselves, and over 90% of respondents had a total alliance score between 0 and 1. The problem of skew also reduces the ability to find correlations between alliance scores and changes in the GDS. Nevertheless, due to less skew in both of these alliance questionnaires, we can account for a higher percentage of variance in SAES scores than was possible with the adult samples.

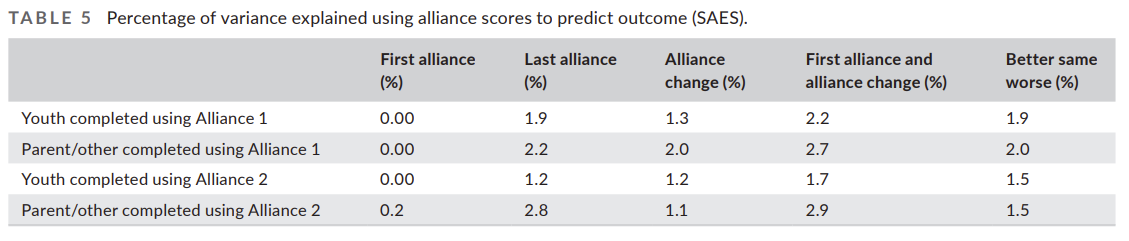

Simple correlations and analysis of variance, using the first and last alliance scores to predict SAES, provide an estimate that alliance accounts for between 2% and 3% of the variance in SAES. While this appears quite small, when applied at a population level, it is meaningful. In contrast, a similar calculation on Questionnaire 1 with an adult population accounted for, at most, 2% of the variance in SAES. Table 5 displays the estimated percentage of variance explained by alliance scores, either singly or in combination, along with the alliance change category of alliance better, same or worse.

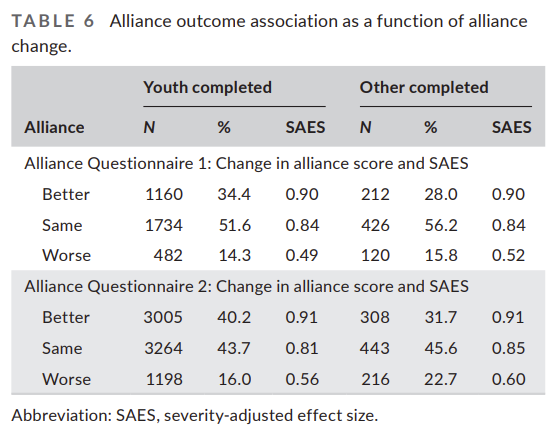

As was found with the adult measures, the correlation between alliance scores or changes in alliance scores with SAES are not linear. More change in alliance does not appear to be more predictive of SAES than very small changes. For this reason, we also treat change in alliance as a categorical variable with three categories: no change, alliance better and alliance worse. Treating alliance change as a categorical variable produced similarly small estimates of the percentage of variance of SAES but is perhaps easier to understand and implement as part of decision-making. It also encourages clinicians to pay attention to very small indicators. An alliance score that changes from 0 to 1 (on a 12-point scale) is associated with a significantly worse outcome. Table 6 presents the SAES scores associated with alliance questionnaires as a function of alliance scores changing in either direction or remaining unchanged.

Over 40% of cases remained unchanged on both alliance scales, which was associated with essentially average change (SAES between .80 and .85). However, the deviation of scores in either direction was associated with statistically significant and clinically meaningful differences in SAES. This is particularly true for the 14% to 24% (depending on the questionnaire) in which alliance worsened. Notably, worse alliance scores are associated with between 0.25 and 0.35 SAES worse results than no change in alliance, while improvement in alliance is associated with between 0.06 and 0.10 larger SAES.

The ability of these two questionnaires to detect improvement exceeded that of the alliance questionnaires completed by adults in therapy for themselves. While over 50% of youth completing Alliance 1 rated the alliance as perfect, over 70% of adults did so on the same items. For adults, only 26% reported any improvement in Alliance 1 scores, compared with over 34% for youth.

As with Questionnaire 1, Questionnaire 2 worsening was associated with a large SAES difference, more than 0.3 SAES. A large percentage of youth completed questionnaires rated alliance as improved compared with Questionnaire 1 (41% compared with 34%), as would be expected due to greater variance at first assessment. However, the percentage improved for other completed questionnaires was comparable with Questionnaire 1, with 32% reporting improved alliance.

The magnitude of SAES difference between no change and some improvement on the alliance scores is 0.15 SAES for the parent/ carer completed questionnaires, but is down to 0.07 SAES for the youth-completed questionnaires. This lower percentage of alliance improved cases appears to be due to a lack of variance at the first assessment for youth-completed Questionnaire 2 when compared to Questionnaire 1. For both questionnaires, the SAES for cases with improved alliance scores was approximately twice as large as those for worsened alliance scores.

4 | DISCUSSION

This study utilised the largest data set to date (N = 12,573) from naturalistic settings to examine the psychometric properties and treatment outcomes associated with two measures of the therapeutic alliance with youth and, where available, with the parent/ carer. Consistent with the findings from our first article, the effectiveness of the therapy provided was large, the alliance measures had ceiling effects and any drop in alliance was predictive of outcome from both youth and parent/carer ratings. Notably, the alliance outcome correlation is not linear, so using a categorical interpretation of alliance measures of better, same or worse can help therapists make sense of alliance scores and the implication for outcome associations.

The large effect sizes for youth treatment found in this study are more comparable with treatment effects found in prior metaanalyses of treatment for internalising disorders (James et al., 2020; Michael & Crowley, 2002; Reynolds et al., 2012). While our data do not permit us to provide information on problem type/disorder, like our previous paper with adults, the effectiveness of therapy in these naturalistic settings is comparable with that from control trials.

The alliance explained up to 3% of the variance in outcome in this data set. Interestingly, this is higher than has been reported in a previous meta-analysis (McLeod, 2011). Surprisingly, the variance in outcome reported here is also larger than the 2% reported in our previous article with adults. However, it is much smaller than the variance reported in Murphy and Hutton (2018), who describe an alliance outcome variance (8%–12%) in adolescent psychotherapy. The results of this study, using naturalistic data only, found that alliance measures explained between 1.7% and 2.9% of variance in effect size depending on the questionnaire and whether completed by the youth or an adult. These results are different from Murphy and Hutton's (2018) results.

However, it is difficult to further evaluate the sources of the differences due to differences in how effect size is calculated, differences in questionnaires, differences in frequency of administration and reliance on studies with relatively small sample sizes. Of course, there is likely much more heterogeneity in our samples in natural settings. Additionally, Murphy and Hutton (2018) did not distinguish between alliance change and alliance measured at a single point in time; when this was controlled for in the most recent meta-analysis (Roest et al., 2023b), findings for the youth alliance outcome correlation were smaller than those reported in a meta-analysis with adults (Flückiger et al., 2018). As such, consistent with our findings in the first article with adults, research from controlled trials and meta-analysis tend to have different variations in findings to data from naturalistic settings.

The most recent three-level meta-analysis of the alliance outcome association in youth psychotherapy (Roest et al., 2023b) found that changes in child–therapist alliance and child outcomes were associated (r= .19; R2= .036). The selection criteria used to include studies in this meta-analysis included the requirement that alliance is measured from at least two of multiple perspectives available, such as child and therapist rating, child and carer rating, and carer and therapist rating.

This is the first meta-analysis to examine changes in the alliance and correlations; however, only a few studies report such findings. The range of effect sizes reported was between 0.1 and 0.59 depending on the combination of alliance questionnaires used. This is, of course, much smaller than the simple pre-/post-SAES used in this study. This would be expected when the reported effect size is the difference between active treatment and control group.

The items used in the therapeutic alliance measures in this study demonstrated ceiling effects, with both the youth and the parent/ carer samples. Findings reflect the limited body of research of youth alliance measure ceiling effects found elsewhere (Bickman et al., 2010; Shirk et al., 2010). We found these ceiling effects in the parent-/carer-rated measures too. Similar to our findings in the adult article, both sets of measures can be interpreted using a categorical approach of better, same or worse. As any drop in alliance from either youth or parent/carer is predictive of effect size, this simple way of assessing the alliance offers the therapist a robust decision-making tool. Again, in these data, a drop from 0 to 1 on a 12-point scale was associated with significant and clinically meaningful effects, regardless of who provided the rating: the youth or the parent/carer.

Furthermore, we have replicated the findings from our previous study with adults in this youth and parent/carer sample. Youth who rated the alliance as better tended to benefit almost twice as much when compared to those who rated the alliance as worsened.

Similarly, this finding also extends to parents/carers who rate the alliance. This triangulation of data across all the samples in both studies lends more validity to the findings and underscores the importance of having parents involved in the treatment process.

Prior research suggests that when parents have a good therapeutic alliance with the therapist, then the youth has better outcomes (De Greef et al., 2017; Roest et al., 2023b; Welmers-Van de Poll et al., 2020). Two meta-analyses demonstrate that parent/carer alliance is predictive of youth outcomes (r= .24; Karver et al., 2019; r= .15; McLeod, 2011). The findings in the present study reflect this outcome; however, caution should be employed with regard to how involved the parent/carer is.

Recent research on the treatment preferences of youth and their parent/carer demonstrates that young people and adults often have diverging preferences for how the treatment is conducted, and how and to what extent the parent is involved (Langer et al., 2021). Considering the predictive nature of the alliance from both the youth and parent/carer perspectives, therapists need to carefully monitor and tend to potential ruptures with both parties. Alliance rupture can have negative impacts on therapy engagement and outcome. Indeed, a large proportion (28% up to 75%) of the treatments in youth mental health care result in premature termination (Baruch et al., 2009; Langer et al., 2021; Midgley & Navridi, 2006). Addressing alliance ruptures with youth may involve a different set of strategies due to their developmental capacity (Shirk et al., 2011).

Alliance ruptures can be conceptualised in two ways. Confrontational and withdrawal ruptures present therapists with different challenges (Eubanks et al., 2018). Withdrawal ruptures present challenges with all clients; however, they may be especially difficult with younger children who cannot verbalise the rupture. In these circumstances, therapists may wish to work through countertransference or find creative strategies to engage the youth.

Confrontational ruptures will be easier to identify due to the direct nature of the communication towards the therapist. In these instances, the therapist will need to contain the situation, and those who demonstrate advanced facilitative interpersonal skills during challenging conversations may be more effective in addressing the rupture, as demonstrated in adult research (Anderson et al., 2016; Eubanks et al., 2018; Heinonen & Nissen-Lie, 2020; Wampold & Flückiger, 2023).

With both types of ruptures, using measures of the therapeutic alliance at every session is another method that is helpful for tracking the client and therapist relationship and improving outcomes. Metaanalyses of systems used to improve outcomes, such as the one used in this study, demonstrate effectiveness (Rognstad et al., 2023; Tam & Ronan, 2017). Considering the attrition rates for youth psychotherapy, and that between 10% and 20% (Brière et al., 2016) of young people deteriorate during treatment, such systems provide an evidence-based way to address some of these issues.

Addressing alliance ruptures with parents/carers may prove equally difficult; however, using alliance measures and feedback systems will offer an evidence-based method to identify and repair ruptures (Tam & Ronan, 2017). Whereas youth may experience the therapeutic alliance as more of an emotional process, research suggests that parents/carers may focus more on tasks and goals. Parents/ carers may also hold different opinions on the nature of the problem (Roest et al., 2023a; Shirk et al., 2010; Zack et al., 2007) and, as such, may also hold ideas about the possible solutions to the youth's problems by way of treatment preferences (Langer et al., 2021).

Considering the predictive nature of the parent/carer alliance rating on youth outcomes, therapists should carefully consider how to capture and accommodate both youth and parent/carer feedback on the alliance.

It is clear from the data that parents/carers are more willing to provide feedback on the alliance when compared to adults in their own therapy; leveraging this feedback is one method of improving youth outcomes.

4.1 | Implications for practice, training and research

The therapeutic alliance is an important evidence-based non-specific component of therapy. Therapists should monitor the alliance and outcomes at every session, with both youth and their parent/carer. Therapists can use standardised measures of the alliance, but be conscious of the limitations due to the skewed distribution. Any drop in the alliance is associated with clinically meaningful change as rated by either the youth or the parent/carer. Due to the highly skewed nature of these measures, change is not linear. Therefore, to help therapists make sense of alliance data, we propose using a categorical approach of better, same or worse to interpret scores.

Managing the potential conflicts in alliance scores provided by youth and their parents/carer will also be important. Training should seek to prepare therapists to identify and repair the various types of ruptures that can occur with both populations. While the use of routine outcome monitoring/measurement-based care is helpful and therapists can be supported to use this evidence-based approach, other training in rupture repair may also be considered. Strategies for engaging youth will likely need to be different, and young people will need more developmentally appropriate strategies that have a stronger emotional element, while parents may experience ruptures based on the goals, tasks and desired outcomes of the youth therapy.

Future research should include efforts to conduct more largescale studies of other widely used measures of alliance and outcome in naturalistic settings rather than clinical trials.

Results obtained may well be different from those observed in clinical trials, but are likely to be more useful in understanding how these measures perform in real-world settings involving a large sample of practicing clinicians.

In the absence of the ability to collect large naturalistic samples, researchers conducting controlled trials are encouraged to provide more pieces of information about the underlying distribution of the alliance measures. It may not be safe to assume that the distribution is normal. Finally, it may be useful for future research to use naturalistic data to examine possible therapist effects in the alliance outcome variation. The meta-analyses cited in this study have not found any impact of this on youth outcomes, and results may differ in routine settings.

4.2 | Limitations

The strength of this study is the large sample in a naturalistic setting. However, this does mean it lacks the rigor of an experimental design, and as such, causality cannot be determined. There was likely variation in how measures were administered and interpreted in this sample. Consequently, in the absence of a randomised trial, internal validity would not be maintained. In addition, the data in this sample are drawn from various routine settings, and as such, we are unable to determine whether there are diagnoses, or other factors, that could hinder how effects in this dataset are interpreted. While we are unable to determine the age of the youth in these data, literacy levels would need to be advanced enough to read and understand the questions on the measures; as such, it is likely that the parent/ carer is not scoring an alliance measure and that the youth is close to or currently going through the adolescence developmental stage.

5 | CONCLUSION

The therapeutic alliance remains an important treatment component in youth psychotherapy; however, our study suggests that the alliance outcome association is less than reported in adult studies and that parent/carer ratings of the alliance are marginally more predictive of outcomes than the youths'. Alliance measures are highly skewed, and as such, interpreting correlations becomes more difficult. We provide a simple, yet effective, categorical approach for interpreting alliance scores and the impact of this on youth psychotherapy outcomes. Finally, we demonstrate in this article, as well as in our previous article with an adult sample, that findings from research controlled trials and meta-analyses are often different to those using naturalistic data.

Author Biographies

Daryl Mahon is a lecturer and researcher. Much of his research focus is on psychotherapy processes and outcome research.

Takuya Minami (Tak), PhD, is associate professor of counselling and psychology and has mainly studied psychotherapy process and outcome during his academic career, particularly with regard to the effectiveness of psychotherapy practised in clinical service settings.

Jeb Brown earned his PhD in counselling and psychology in 1978 and has spent the preceding decades focussed on improving psychotherapy outcomes through the use of feedback-informed data.